Almost everyone knows that it’s best to start any significant writing project with an outline. But what many people don’t know is that it’s even better to start with a nonlinear outline. What is a nonlinear outline? Well, it’s kind of an organized brainstorm, or “mind dump.” Nonlinear outlining is a great way to get all of your thoughts down before you start organizing; it lets you think in a more unrestricted way, which gives you all of the benefits of a brainstorm.

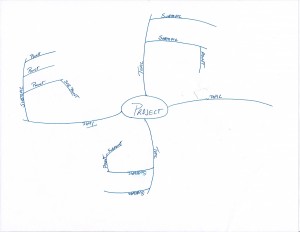

So, how do you do a nonlinear outline? It’s easy. Start with a blank sheet of paper, draw a small circle (or oval, or square if you’d like) in the middle and write your project’s title in that circle.

Then you start letting your brain go wild. For any main topic, draw a line from your center circle, writing the topic on the line. Then, for any subtopic, you draw a line off of that line. Then the same for each point and sub-point. Soon you’ll have a pinwheel of brainstorming. Either set a time limit, or continue to add to your nonlinear outline until you can’t add anything else. Once you think you are finished, force yourself to add two more branches; these can be lines off of any level of your pinwheel.

Then you start letting your brain go wild. For any main topic, draw a line from your center circle, writing the topic on the line. Then, for any subtopic, you draw a line off of that line. Then the same for each point and sub-point. Soon you’ll have a pinwheel of brainstorming. Either set a time limit, or continue to add to your nonlinear outline until you can’t add anything else. Once you think you are finished, force yourself to add two more branches; these can be lines off of any level of your pinwheel.

Ultimately, you’ll end up with something like the second image here. Please don’t edit yourself as you complete your nonlinear outline; the whole idea is to get all the ideas you can possibly think of down. Only after you’ve completed your nonlinear outline do you move on to a traditional, linear outline. Wait until you are moving from your nonlinear outline to a traditional outline to edit yourself. It is during this step that you can move points and sub-points from one topic to another, combine topics, or eliminate some of your nonlinear outline altogether. The nonlinear outline is the time to let your brain run free. Give your ideas structure and make a workable document plan at the traditional outline stage–not before.

Ultimately, you’ll end up with something like the second image here. Please don’t edit yourself as you complete your nonlinear outline; the whole idea is to get all the ideas you can possibly think of down. Only after you’ve completed your nonlinear outline do you move on to a traditional, linear outline. Wait until you are moving from your nonlinear outline to a traditional outline to edit yourself. It is during this step that you can move points and sub-points from one topic to another, combine topics, or eliminate some of your nonlinear outline altogether. The nonlinear outline is the time to let your brain run free. Give your ideas structure and make a workable document plan at the traditional outline stage–not before.

I wish I could claim credit for the nonlinear outline, because it is something that has truly enhanced my writing, especially for long or in-depth projects. Alas, it is one of the many things I learned from legal writing guru Bryan Garner; it is taught at his seminars and is included in many of his publications. But do not let the fact that it is taught by a legal writing master fool you into thinking it is only beneficial for legal or other persuasive writing. It is a great tool for any project, and I recommend it to anyone who is preparing for a writing project.

Let your wild side come through into your writing a bit. Color outside the lines.

This isn’t meant to be a Stuart Smalley, “I’m good enough; I’m smart enough; and doggone it, people like me” affirmation. What I am saying is that your writing will always be its best when it comes out in your voice. When practicing law, I’ve often had to write things to be signed or argued by other people. This is hard for me. The reason is not that the law or argument changes, but that the voice has to change. If a document is going to be argued or presented by someone else, it has to be written in that person’s voice. If it’s not, the argument will not go smoothly and the person arguing will have a hard time presenting the things as set forth in the document. When I have to write for a voice other than mine, it feels unnatural. I wind up having to say things in a way that is foreign to the way my mind works. I’m never very happy with something that I’ve written for someone else’s voice, because it just doesn’t work for me. And if the person who it was written for doesn’t spend some time editing and adjusting the document to his or her own voice, it won’t feel natural to them either, and no one will be happy with it.

This isn’t meant to be a Stuart Smalley, “I’m good enough; I’m smart enough; and doggone it, people like me” affirmation. What I am saying is that your writing will always be its best when it comes out in your voice. When practicing law, I’ve often had to write things to be signed or argued by other people. This is hard for me. The reason is not that the law or argument changes, but that the voice has to change. If a document is going to be argued or presented by someone else, it has to be written in that person’s voice. If it’s not, the argument will not go smoothly and the person arguing will have a hard time presenting the things as set forth in the document. When I have to write for a voice other than mine, it feels unnatural. I wind up having to say things in a way that is foreign to the way my mind works. I’m never very happy with something that I’ve written for someone else’s voice, because it just doesn’t work for me. And if the person who it was written for doesn’t spend some time editing and adjusting the document to his or her own voice, it won’t feel natural to them either, and no one will be happy with it.

As Tommy neared the stop sign, he hit his brakes and looked both ways to see if there was any traffic at the intersection. Because it was dark, Tommy could not see Billy’s sport utility vehicle, which was also approaching the intersection. As Tommy pulled into the intersection, he heard the sound of a car horn and looked up to see Billy’s sport utility vehicle, with a panicked Billy behind the wheel, also entering the intersection. Both of the drivers, who were trying to avoid a collision, applied their brakes…

As Tommy neared the stop sign, he hit his brakes and looked both ways to see if there was any traffic at the intersection. Because it was dark, Tommy could not see Billy’s sport utility vehicle, which was also approaching the intersection. As Tommy pulled into the intersection, he heard the sound of a car horn and looked up to see Billy’s sport utility vehicle, with a panicked Billy behind the wheel, also entering the intersection. Both of the drivers, who were trying to avoid a collision, applied their brakes… Tommy neared the stop sign. He hit his brakes, looking both ways. It was dark. Tommy did not see Billy’s SUV approaching. Tommy pulled into the intersection. He heard a car horn. Looking up, Tommy saw Billy’s SUV entering the intersection. Billy was panicking. Tommy applied his brakes. Billy applied his brakes. Both tried to avoid the collision…

Tommy neared the stop sign. He hit his brakes, looking both ways. It was dark. Tommy did not see Billy’s SUV approaching. Tommy pulled into the intersection. He heard a car horn. Looking up, Tommy saw Billy’s SUV entering the intersection. Billy was panicking. Tommy applied his brakes. Billy applied his brakes. Both tried to avoid the collision…

Rest in peace, literally. It’s not the first time, but it is one of the most recent. The misuse of the word “literally” as a substitute for “figuratively” has become an accepted definition. Many major dictionaries, including perhaps the most-used modern dictionary, dictionary.com, now include some version of “figuratively” as an accepted use of the word “literally.”

Rest in peace, literally. It’s not the first time, but it is one of the most recent. The misuse of the word “literally” as a substitute for “figuratively” has become an accepted definition. Many major dictionaries, including perhaps the most-used modern dictionary, dictionary.com, now include some version of “figuratively” as an accepted use of the word “literally.”